Introduction to I2C protocol, reading and writing in 24LC memories

I2C (spelled I squared C) is a standard that allows for easy communication between multiple devices (microcontrollers, memories, computer monitors, sensors, converters, and many other smart devices).

It only requires two signals: one for clock and one for data (as well as the common ground). Originally designed by Philips, it has a maximum speed of 100 Kbits per second, but some devices can be interfaced at a higher speed.

It’s a serial type bus (the bits travel one after the other) and synchronic (one of the signals is used to synchronize the master and slave)

The data signal is called SDA, while the clock signal is SCL o SCK. As they are open collector signals, two pullup resistors are needed, in the range from 2 Kohm to 50 Kohm.

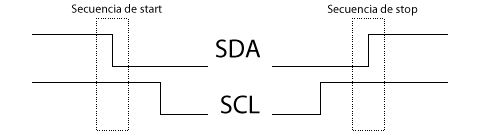

The protocol features different signals, which are sent by the master device. In a halt state, both signals remain as a logic high.

The START and STOP sequences are used to signal the beginning and end of a request to a slave device. Those are the only sequences that can have an SDA change while SCK is high:

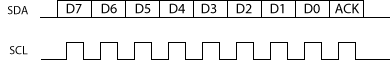

The data is transmitted in 8 bit sequences, in a sequencial way: starting by the most significant bit, the bits get placed in the SDA line, and the SCK line is pulsed (by sending a rising and falling edge). Every 8 sent bits, the receiver adds an acknowledge bit, which indicates if it’s ready to receive more bytes. If it’s 0, more bytes can be sent, and if it’s 1, a STOP signal should be issued to end the transfer.

Typically, I2C devices have a 7-bit address (128 different slave devices can stay in the same line), so before starting any transfer another packet must be sent, containing the 7 bits of the address and an extra bit, indicating if a write (1) or read (0) is desired.

Most applications that need a small non-volatile memory can use 24LC series EEPROMs. They are very useful devices and can be used to store configuration data or keep a small log of sensors. Because they use I2C, it only requires two extra I/O lines, so they can be used with smaller microcontrollers.

This series of memories come in a range of 128 bytes to 1 Megabyte. For instance, a 24LC256 has 256 kilobits (32 KB) available byte and costs less than a dollar.

They aren’t designed for continuous use or lots of writes (they support at least 1 million write cycles), so they are limited to fixed data or information that doesn’t need to change much. Because they have a pretty big delay while writing (5 ms) they can’t be used to replace RAMs.

Doing a write or read command is quite easy: the microcontroller can have a I2C module or it can be bit-banged in software. Each memory has 3 extra pins, which allows connecting more memories to the same I2C bus (each one with a different address).

Writing a single byte

The process is the following:

- Make a START sequence

- Send 1010XXX0, where XXX is the direction of the IC to use, wait for ACK

- Send the low byte of the address to be written, wait for ACK

- Send the high byte of the address to be written, wait for ACK

- Send the byte to be written in the specified address, wait for ACK

- Make a STOP sequence

Writing a page (multiple writes in the same command)

The memories tend to support page writing: writing more than 1 byte in the same command. This can be used to reduce the write time, needing to wait only 5 ms per written page. The memories usually support 64 byte pages, and in most cases, the writes can only start in an address multiple of 64.

The process is similar to the single-byte one, but more bytes are sent before making the STOP signal:

-

Make a START sequence

-

Send 1010XXX0, where XXX is the direction of the IC to use, wait for ACK

-

Send the low byte of the address to be written, wait for ACK

-

Send the high byte of the address to be written, wait for ACK

-

Send the byte to be written in the specified address+0, wait for ACK

-

Send the byte to be written in the specified address+1, wait for ACK

-

Send the byte to be written in the specified address+2, wait for ACK

-

…

-

When finished, send a STOP sequence

It’s possible to write any amount of data up to 64 contiguous bytes, always closing the transfer with a STOP signal.

Waiting for end of writing

After making a write request, the memory won’t reply to commands for around 5 ms, until it finishes writing the data. It’s possible to detect if the memory is busy by sending the start of a write request. If the memory doesn’t answer with an ACK, it’s still busy.

Single Byte Read

Reading a byte from a specified address is easy:

- Make a START sequence

- Send 1010XXX0, where XXX is the direction of the IC to use, wait for ACK

- Send the low byte of the address to be read, wait for ACK

- Send the high byte of the address to be read, wait for ACK

- Make a START sequence

- Send 1010XXX1, where XXX is the direction of the IC to use, wait for ACK

- Read byte, don’t send ACK to the memory

- Send a STOP sequence

Multiple Byte Read (Sequential)

As well as writing multiple bytes, reading multiple adjacent bytes is supported.

- Make a START sequence

- Send 1010XXX0, where XXX is the direction of the IC to use, wait for ACK

- Send the low byte of the address to be read, wait for ACK

- Send the high byte of the address to be read, wait for ACK

- Make a START sequence

- Send 1010XXX1, where XXX is the direction of the IC to use, wait for ACK

- Read byte 0, send an ACK to the memory

- Read byte 1, send an ACK to the memory

- Read byte 2, send an ACK to the memory

- …

- When no more bytes need to be read, send a STOP sequence

Some other types of I2C devices are the widely used RTC (real-time clocks) such as the DS1307, which allows for timekeeping and making clocks or alarms. They also tend to have an internal RAM or EEPROM memory. Manufacturers also sell I2C non-volatile RAMs that work in a similar way to the memories described in this article. The main difference being that they support Unlimited writes (they don’t wear out in time).