Introduction to GLSL Shaders

This doesn’t pretend to be a complete tutorial about shaders but a simple explanation on how to make some visual effects typically used in games.

A shader is a small program that executes directly on the GPU (graphics card). This allows doing complex effects with little impact on performance. CPUs aren’t suitable for graphics, vector, and matrix math, while GPUs have native instructions for those, while also being suitable for parallel works.

Nowadays, nearly all graphic cards (including the low-tier ones) support some type of shaders. They can also be used to do normal data processing, particularly operations that can be easily parallelized. For that type of application, it’s best to use OpenCL and not standard shaders.

In most graphics applications, there are three types of shaders:

Vertex Shaders: They execute once per vertex of the element to be rendered. They can be used to move the vertices, for instance, to create a distortion effect (ocean waves), or making skeletal interpolations. Their return value is the transformed vertex position.

Pixel Shaders (in OpenGL they are called Fragment Shader): they are executed once per each visible fragment of the image (the actual amount ends up depending on the camera view, object sizes, and other factors). Their return value is the color of the resulting pixels. With the help of vertex shaders, they can be used for simulating illumination, techniques such as cell shading, bump mapping, and lots of post-processing filters such as blur, depth of field, motion blur, bloom, hdr, etc.

Geometry Shaders: they execute once per each face of the object to be rendered. They have a different output than the other two since they can output new vertices. That allows them to do more complex effects such as grass, hair, projected shadows, reflections, without needing for the CPU to generate the new vertices.

There are various languages to develop shaders, this tutorial focus on GLSL because its style is similar to C/C++, and it’s very easy to learn.

To try the codes, it’s possible to use a tool like RenderMonkey or ShaderToy (online service). In this tutorial, we’ll create a simple effect: an ambient light.

Ambient light denotes every light that’s present in a scene. In real life, it doesn’t exist, but in graphics, it’s always beneficial for every object to be lit, even if they have no near lights. This is required because the light bounces aren’t calculated, typically engines do not raytrace as that’s too slow.

The basic formula for ambient light is:

I = Object.AmbientColor * Light.AmbientColor

Where both colors are 3 coordinate vectors (R,G,B), corresponding to the object color and the ambient light color. I is the resulting color.

Source code:

Vertex Shader:

void main() {

gl_Position = ftransform();

}

Pixel Shader:

void main(){

vec4 color = gl_FrontMaterial.ambient * gl_LightSource[0].ambient;

color.a = 1.0;

gl_FragColor = color;

}

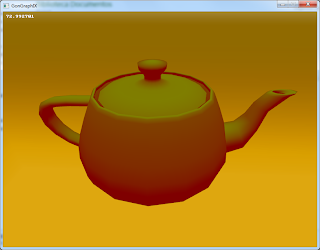

Screenshot:

As can be seen from the image, the ambient light is purely red (1.0,0.0,0.0) and the object color is gray (0.5,0.5,0.5). Hence the output pixels get that color (0.5, 0.0, 0.0).

Directional lights

Directional lights are supposed to be at an infinite distance, so they don’t have a position, only a direction, since all of their rays are parallel.

The diffuse component of a light is the first term of the approximation, where it’s assumed that the intensity depends only on the normal of the surface in that point and the direction vector of the light.

The reflected light value will be higher when the angle between the light and the normal to the surface is smaller. When the vectors are parallel, the diffuse component will have a maximum, and when they are orthogonal the contribution will be zero.

To calculate the angle between the light and the normal, the inner product (dot product) can be used. It returns |LightDir| x |Normal| x cos(angle).

To avoid having to divide by both norms, both vectors are normalized before doing the dot product. Since the cosine of the angle can be negative, we clamp the value to a number between 0 and 1.

The formula looks like this: I = Object.AmbientColor * Light.AmbientColor + Object.DiffuseColor * Light.DiffuseColor * clamp(dot(Face.Normal, Light.Direction))

Source code:

Vector Shader:

varying vec3 normal;

void main()

{

normal = gl_Normal;

gl_Position = ftransform();

}

Fragment Shader:

varying vec3 normal;

void main()

{

vec4 color = gl_FrontMaterial.ambient * gl_LightSource[0].ambient + gl_FrontMaterial.diffuse

* gl_LightSource[0].diffuse * clamp(dot(normalize(gl_LightSource[0].position), normalize(normal)));

color.a = 1.0;

gl_FragColor = color;

}

Screenshot:

The light used is green, shining from above, and it can be seen that the places more lit are those whose normal is similar to the light direction.

A varying type variable is used to pass data from the vertex shader to the pixel shader (in this case the normal of each vertex), which implies that OpenGL interpolates it. This allows for a per pixel illumination. If the color was calculated in the vertex shader and then interpolated, it would look different (second screenshot).

Types of Lighting

Static Lighting: The light effects (as well as the shadows) are prerendered when the models are built, and then combined with the diffuse texture of the object, as well as the ambient occlusion. This method mostly works for still rigid objects, and it’s impossible to move the lights since the shadows are pre-baked as textures. Creating the textures may take a long time since raytracing-like algorithms are used, but a higher realism may be achieved.

Dynamic Lighting (per vertex): This is the basic illumination included in older OpenGL. The normals of each vertex are used to calculate the incidence of light, and then the colors are interpolating along the face.

Dynamic Lighting (per píxel): Similar to the previous one, but the normal is interpolated instead of the color. Has a higher quality than per-vertex lighting.

Deferred Lighting: If multiple lights are desired (more than 4/5), both previous methods are quite slow, because the scene has to be rendered multiple times and the lights should get accumulated. The idea of this method is to store the information of the scene (depth map, normal, diffuse texture of each pixel of the screen). And then lots of simple passes use that information to calculate the contribution of each light. This method is quite fast, especially when it’s an indoor map with lots of point lights or spotlights. As a disadvantage, this method doesn’t allow for translucid materials nor for antialiasing, and it needs a high amount of GPU memory, proportional to the resolution of the screen.

There are other methods based on the last one, that use the precalculation of the screen as seen by the camera to avoid multiple geometry passes.

Some methods to render shadows:

Pre-baked shadows: Calculated while doing the map and static objects, they can’t be moved, deform or destroy, and the light positions have to remain static to keep the illusion.

Fake shadows: Below each object that needs a shadow a small sprite is drawn, typically a round black image with blurred borders. It’s a very fast way to draw shadows, but not really used because it’s not realistic.

Shadow mapping: The scene is rendered from the light viewpoint, and then in the eye object the depth that the camera sees gets compared to the depth seen by the light. If one is greater than the other, it’s shadowed, otherwise it isn’t. It is a relatively fast method, and can be used for point lights with a technique such as dual paraboloid mapping and other methods such as cascaded shadow maps.

Shadow volume: This method finds the borders of the geometry as seen by the light, and then projects it to the back of the scene. It isn’t very used since it heavily depends on the geometry, and more vertices are generated for the shadows.

There are other methods based on shadow mapping that allow for better quality and higher performance. Some of them split the shadow map into multiple ones, in order to keep a constant quality for far and near shadows.